Dear Rabbi Joshua,

My name is Michael Rodriguez and I’ve often observed that some Jewish men have distinctive side curls. Could you explain the reason and significance behind these curls? Thank you for your insights.

The Roots of Payot in Jewish Law

Dear Michael,

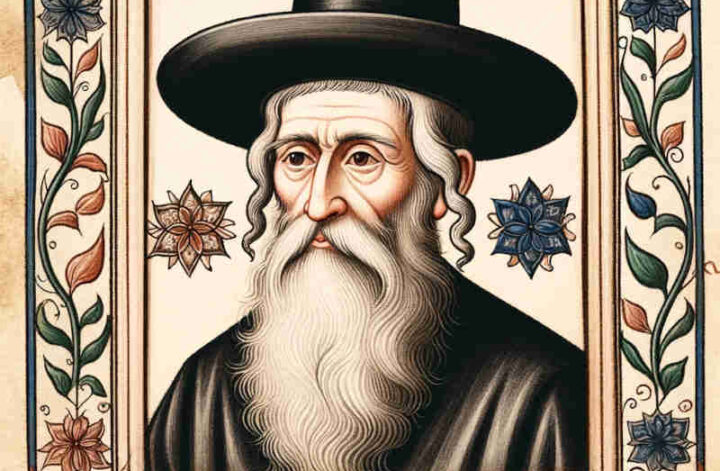

Thank you for your thoughtful question. The side curls, known as payot in Hebrew, are worn by some Jewish men as a symbol of piety and adherence to Jewish law. The practice of growing payot comes from a literal interpretation of a commandment found in the Torah, in the book of Vayikra (Leviticus) 19:27, which states: “לֹא תַקִּפוּ פְּאַת רֹאשְׁכֶם וְלֹא תַשְׁחִית אֵת פְּאַת זְקָנֶךָ” — “Do not round off the hair at the temples or mar the edges of your beard.”

Payot Through the Ages

Historically, this commandment has been interpreted in various ways by different Jewish communities. The Talmud, in Masechet Makkot 20b, discusses the parameters of this mitzvah, advising against shaving the corners of one’s head. In more recent times, the practice of growing payot became particularly associated with certain Hasidic communities, who emphasize the mystical aspects of fulfilling the commandments with joy and physical expression.

Spiritual Significance and Contemporary Practice

The wearing of payot is not just a matter of tradition, but one of spiritual expression as well. Many see it as a reminder of the covenant between God and the Jewish people, a physical embodiment of the commandments, and a symbol of their distinct identity. In today’s diverse Jewish population, the practice varies, with some men choosing to wear their payot long and conspicuous, others tucking them behind their ears, and still others interpreting the commandment in a way that does not require growing them at all.

I hope this provides you with a clearer understanding of the practice of growing payot and its place within Jewish life and law.

Warm regards,

Rabbi Joshua